Celebrations of ephemeris are often a mere formality. But in the case of the Modern Art Week, this remembrance is unavoidable. After all, if we keep looking at that past after so long, it's because something of it survives and makes us think not only about our roots, but about how they help define our future. There is something singular in these festivities around the 100th anniversary of the event, a desire to better understand its meaning. And there is also a kind of anxiety, a desire to revive a spark that helps us to illuminate the present, finding some breath that helps us face contemporary anguish and paralysis – seeking with a mixture of nostalgia and fatigue to understand and defend transformative projects. , who defied the rules and proposed to abandon the stale staleness in search of new models of thought and production.

The list of meetings, exhibitions, book and magazine launches that revolve around the three-day meeting held at the Municipal Theater of São Paulo in February 1922, which over time became the founding myth of national modernity, is enormous. And it just grows. There are countless approaches adopted and it is a relief that in this centenary there is little room for frozen and merely laudatory looks. It is true that such a profusion of studies and presentations leaves room for both long-term debates and neighborhood fights that have long been outdated, but that act as bait for clicks and likes in our world of digital warmongering.

The contrast between the volume of thought contained in the exhibitions, catalogs and anthologies and the shallow aspect with which the mainstream media has been treating the event is glaring, as the little that has been seen in the press on the subject is riddled with historical errors, usually called fake news, which perpetuate widely repeated misconceptions such as the alleged participation of Tarsila do Amaral in the Semana (she was in Paris and only approached the group later) or the conspiratorial idea that the boos heard during the presentations at Municipal would have been hired cheerleaders by the artists themselves to enhance their performances, something that recalls the daily manipulations of contemporary times and which was vehemently denied by Oswald de Andrade in Confessional Diary, a work republished by Cia. das Letras along with other works of his authorship.

Despite accusations of excessive paulistocentrism and a certain effort to point out a series of gaps and contradictions present in that group, there is an increasing consensus among researchers that the importance of the Week is more symbolic than real. It is also no longer news that many of the participating authors only consolidated their modernity in the future and that it is necessary to expand the look beyond São Paulo, beyond the milestones of 1922 and to social segments ignored by the modernists in the period. This does not take away from the emblematic importance of the Week, as a moment of condensation of a slow and more comprehensive process of modernization in the country. Perhaps this more attentive and diverse observation confirms that there was something premonitory in the answer given by Manuel Bandeira to a reporter in 1952. Said the poet, whose poem the frogs, read during the week, was booed: “I think it's perfectly unnecessary to celebrate the thirtieth anniversary of the Week. Waiting for the centenary. If in the year 2022 they still remember it, then yes.”

Visions that transform

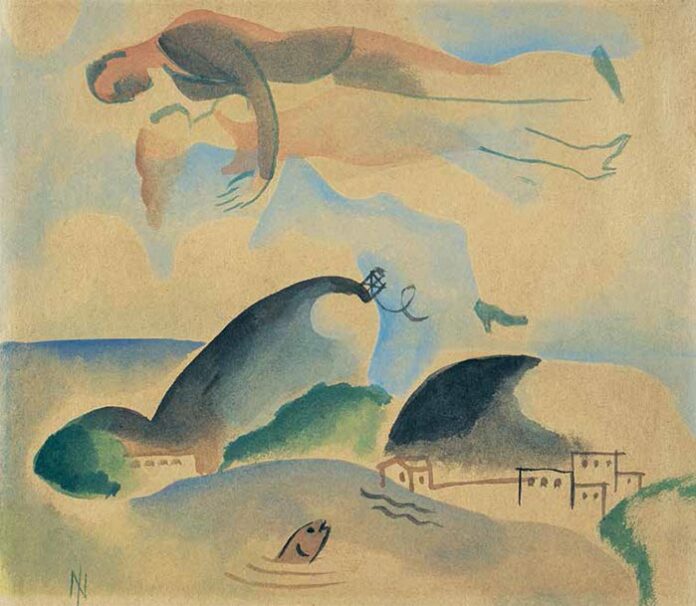

The kick-off for reflections on the week's developments began last year, with a series of meetings sponsored by a consortium of cultural institutions in São Paulo: Pinacoteca do Estado, São Paulo Museum of Contemporary Art and Instituto Moreira Salles. Illuminating blind spots, placing the Week in a less mythical and more real context, inserting it in a process of formation of a more plural national culture, were some of the objectives of the event, which unfolded in 10 meetings between March and December, with dozens of guests and that can be seen on the organizers' Youtube. It was also in 2021 that many museums (MAM-SP, MAC-USP and Pinacoteca, among them) preferred to hold their exhibitions around modernism, disassociating themselves from the obligation to participate in the celebratory calendar and opting for a less nuclear perspective. The Museum of Modern Art stood out with its exhibition and catalog Modern where? Modern when?, curated by Aracy Amaral and Regina Teixeira de Barros, and which not by chance adopted the phrase: “The Week of 22 as motivation”, evidencing the importance of the Week as a fundamental element, but not necessarily the locomotive of the process of “ aggiornamento” of Brazilian art, which unfolded in different ways in time and territory.

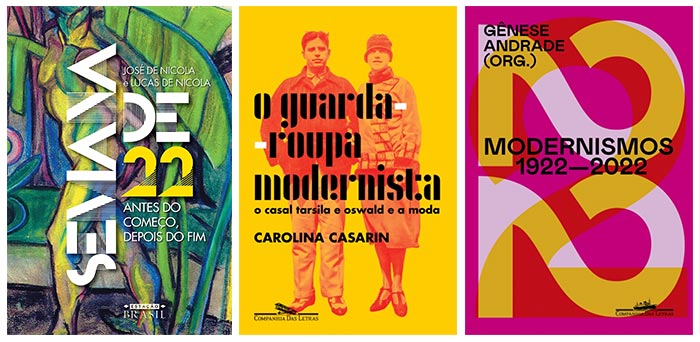

In fact, the terms adopted in the titles of the numerous publications already released or still in press on the subject are very illustrative: Week 22: Before Start, After End (Brazil Station), Modernity in White and Black e Modernisms 1922-2022 (Cia. das Letras) translate in a very synthetic way some of the fundamental questions that constitute the backbone of how the São Paulo movement is being thought of today.

After all, how does 2022 see 1922? And how has this vision been transformed over time, helping us to understand more about the historical moment and also about the current moment? As Ana Maria de Moraes Belluzzo writes in a text published in the catalog of Modern where? Modern when?, it is a collective project of national interpretation, which places us in front of different modernisms. She reminds us that we cannot forget that, in addition to the Semana de 22, we have other moments of great historical density that helped to compose our modernity, such as the Revolutionary Salon of 1931, in which great names of art participated in even greater intensity. national (such as Cícero Dias, Ishmael Nery, Guignard, Goeldi…). As other prominent events in the modernist field, it is also possible to mention the Regionalist Congress, held in 1926 in Recife, in addition to a series of publications, magazines or manifestos published in different places in Brazilian territory without the Week being even mentioned. “Modernism cannot be seen as a canon, but rather as a moment of very great wealth,” she says. “I don't know why these people keep wanting to know where it starts. Don't start, popcorn”, she jokes. “Whoever asks this question thinks that history is a linear process”, explains the researcher, who this year organizes the program Modernism Today, a series of 11 episodes that discuss the emergence and development of modernism, an initiative of Paulista Academy of Letters.

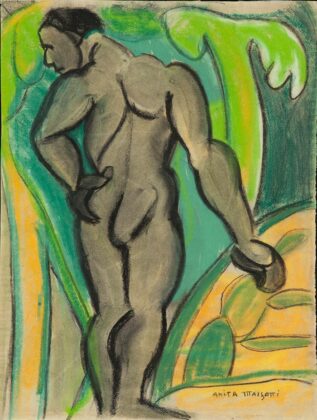

Nobody really knew what that was in 1922, explains Thiago Gil de Oliveira Virava, author of A Boxer in the Arena: Oswald de Andrade and the Visual Arts in Brazil, to be released this year by Biblioteca Brasiliana and Sesc, along with other award-winning works that deal with our double celebration of the year: the centenary of the Week of Modern Art and the bicentennial of Independence. At that moment, according to him, what differentiates the movement is that there is a group, which began to form around the Anita Malfatti exhibition in 1917, whose participants defend each other and prepare for this offensive. Evidently there was a political articulation and it was not for nothing that they chose the year 1922 (they even considered organizing the Week in 1921, but the coincidence with the celebrations of the centenary of Independence made them postpone the execution). The project was gradually built up, based on both an articulation with the Parisian avant-gardes – with Tarsila and Oswald later, between 1923 and 1928, acting as a kind of ambassadors in the French capital – and the attempt to create a national network of exchange and interlocution. “Which does not mean that they were determining what modernism would look like in those places,” he warns.

A theme that never ends

“1922 is a landmark of modernism, if it was built a posteriori, it doesn’t matter” highlights Lauro Cavalcanti, director of Casa Roberto Marinho and curator of the show Modern Flows, on display at the Instituto Carioca until June. Bringing together works by the Week's unavoidable names and lesser-known artists today, such as Roberto Rodrigues, brother of Nelson Rodrigues who was murdered at the age of 23 by a journalist - who was outraged by the publication of a cartoon alluding to her alleged betrayal -, the exhibition it has moments of great actuality and defense of modernist ideals. “More than ever in Brazil it is necessary to celebrate modernity. We are in a period of darkness and this resistance, this moment of strength of possibilities, of openness is fundamental”, he concludes.

“This is a never-ending topic”, says Gênese Andrade, organizer of the anthology Modernisms 1922-2022 and that defines the Semana as the first performance of great repercussion in the country. “As performances tend to be, it was very little seen. There is talk about a scene about which there is only a blurred memory, a fame without ballast many times,” she says. Perhaps it is because of these fluid contours that it lends itself so well to the role of synthesizing a disparate, scattered, prolonged and unequal process as was the penetration of modern thought and language in Brazil.

Another interesting aspect of this centenary, which will possibly bear fruit in the future, is the effort to bring together thinkers from different backgrounds, areas of knowledge, regions of the country and even from different generations. Memories, reflections, questionings compose a diverse panorama, sometimes even contradictory, but complementary, as it is possible to discover in the pages of the anthology. There are gathered from studies that help to understand the symbiosis between the Week project and a larger project to elevate São Paulo to national political and economic leadership. Felipe Chaimovich, for example, makes an interesting analysis of the Prado family's articulations with the ways of seeing and sponsoring Brazilian arts. And Luiz Ruffato illuminates the fundamental experience of the literary magazines that sprang up everywhere in Brazil in the first half of the 20th century. Criticism and reflections on the elitist and exclusionary character of the movement (in racial and genre, especially in literature), but the collective effort to try to understand how the interpretations around the São Paulo movement became different and more complex over time predominates.

Therefore, the association between the Week and the idea of avant-garde is diluted. To use a military term other than the front platoon (after all, modernity was imported from France, years later, and adapted in different ways across the country), one can adopt the cannon metaphor, as an instrument that launches a projectile far forward, as a weapon of prolonged effect.

Alternative modernisms and popular culture

There are, especially in São Paulo, options of all kinds for those who want to dive into this universe. The exposure Once upon a time the Modern, on display at the Fiesp Cultural Center and organized in partnership with the Instituto de Estudos Brasileiros (IEB), has been identified as the largest exhibition on Brazilian modernism ever held, with more than 300 works and documents that are normally preserved from the public in the reserves techniques of the USP institution, which has among its treasures the archives and collection of Mário de Andrade, material extensively revisited in publications, studies and theses.

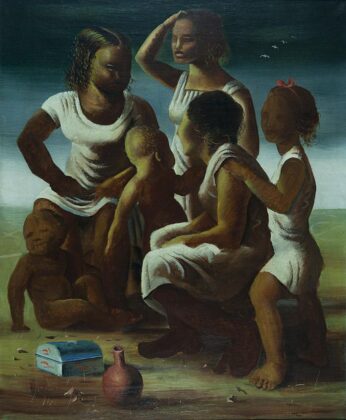

Also with stunning dimensions there is the exhibition damn it, which is part of Sesc-SP's celebrations around the Week and which brings together an expressive set of more than 600 works, made by 200 artists from different regions, generations and languages. The exhibition provides important space for more popular forms of expression such as print, photography and popular art, which are usually less valued by the literate elite, but which play a fundamental role in the dissemination of modernity in the country.

The strength of popular culture and the erasure of the racial question are also important elements of the book. Modernity in Black and White, authored by researcher Rafael Cardoso. “The names of our canon derive almost exclusively from the elitist spheres of literature, architecture, art and high music, while the alternative modernisms that sprang from popular and mass culture are forgotten or ignored”, writes the author who analyzes, among others, the cases of Arthur Thimoteo da Costa and Lima Barreto, black painter and sculptor, both dead in 1922, whose “alternative” modernism was long ignored. But as Cardoso himself says, “the past always finds a way to haunt the present again”.

The racial issue, which in recent years has yielded some of the most innovative reinterpretations of the country's history, was also markedly present in the cycle of events organized by the Municipal Theater itself, stage of the actions of 100 years ago. In a speech marked by denunciation and reflection, the poet and researcher Allan da Rosa deconstructed myths and not only clearly demarcated the elitist character of the event, but also described what was happening in the city of São Paulo while the elite fought on the theater stages. Averse to the celebration of the popular as an explosion of carnival joy, Allan spoke about urbanity, exclusion, opacity and forgetfulness. According to him, just remembering that the Week was held under the sponsorship of the coffee aristocracy, allied to financial capital and commercial capital, is to rain on the wet. It is important to look at urban culture, ignored, present in work corners, in the kitchen, in everyday life. It is important to think about those people who did not even know about the Week, because it had “a very white, terribly white look, despite praising carnivalized meetings”, he concludes, recalling that at the beginning of the century, the project in force since the end of the 19th century was whitening. of the nation. And he warns: “When we exchange a solemn imperial repression for another repression, it is not a de-repression”.

modernist women

Modernism is not only made of Mário and Oswalds, Anitas and Tarsilas. Evidently, the Andrades, as many call the two greatest writers of modernism and who made their first appearance with Semana de 22, are unavoidable. After all, they have developed over decades some of the most solid cultural projects for the country, suffice it to mention the Anthropophagic Manifesto, formulated by Oswald in 1928, and the entire project to survey and preserve the national heritage led by the author of Macunaima. Mário, by the way, is one of the few to be remembered in these celebrations with a solo exhibition, on display at the Afro Brasil Museum.

In the case of the two painters, it is interesting to note how they were, at the same time, elected to a prominent role in Brazilian art due to their proximity to the ideas of the Week, but at the same time they paid a price for it. As Ana Paula Simioni demonstrates in modernist women, his involvement with the group ended up causing the gaze on his productions to be restricted to the initial period, with the rest of his work being for a long time seen as decadent or inferior. They also end up being framed in narrow models, Anita being eternally framed in the role of “martyr”, victim of the attacks of Monteiro Lobato in the critique of his 1917 exposition, and Tarsila in the role of “muse”, of the beautiful and seductive woman.

According to Simioni, one of the positive effects of celebrations like this one around the Week would be a recovery of modernism as a research topic, with emphasis on studies that seek to rescue artists or less studied phases, especially among women artists who have been relegated to a role for a long time. secondary or non-existent in the history of art. One of those figures who, according to her, deserves to be better known is Nair de Teffé, the first caricaturist in Brazil and possibly the world, who married none other than President Hermes da Fonseca. Among the many merits of Nair is that of having taken the jackfruit cutter, popular composition by Chiquinha Gonzaga, inside the Catete Palace in 1914.

“We fight over the past because we live in a present of destruction”, says Ana Paula, in line with the idea defended by Lauro Cavalcanti that more than ever it is necessary to celebrate modernity, as a way of counteracting the destruction of its legacy – it is enough see the dismantling of cultural structures that have been strategically orchestrated by the current government, such as the dismantling of the Instituto do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional (IPHAN), one of the most important legacies of Mário de Andrade and his generation – without falling into the trap of using vital contemporary issues to, anachronistically, make demands on the agents of the past. After all, it is necessary to be aware that, as Thiago Virava says, we have an “incomplete, flawed and full of holes modernity”.