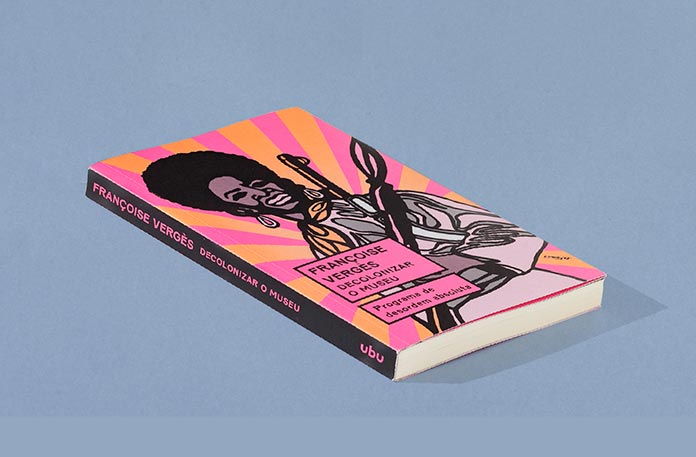

With Decolonize the Museum – disorder program Absoluta (Ubu, 2023), the French activist and thinker Françoise Vergès makes a precise analysis of the current situation of museums which, if on the one hand they seek new practices contrary to the colonialism that is in the very gene of their emergence, continue to use the same hierarchical system and patriarchal as always. “We need to go further”, she argues in an exclusive interview in São Paulo, at the beginning of last October, when she came for the launch of the publication and several conversations in several states across the country.

Under the impact of Choreographies of the Impossible, the first São Paulo Biennial with a majority black curatorship, in addition to several exhibitions in the city that seek the meaning of reparation, Vergès says: “It’s not enough.”

As she argues in the book itself, “it is not enough to exhibit 'decolonial' works (…), diversify what is hung on the walls, talk about preservation and conservation in a state of permanent war against subalterns and indigenous people”. It seems here that she is referring to the Masp controversies surrounding the exhibition Brazilian Stories, last year, but she says she was not aware of the case. In fact, however, there are not many differences between the arrogance of the French museums to which she is accustomed and which she reflects on in the publication and that of Avenida Paulista.

The book also addresses other urgent issues now, such as the poor working conditions reported by employees of the São Paulo Biennial: “It is necessary to create a place where the working conditions of those who clean, monitor, cook, research, administer or produce are fully respected; where hierarchies of gender, class, race and religion are questioned.”

Read below some of Vergès' reflections after visiting the São Paulo Biennial and Ocupação 9 de Julho, which hosts the exhibition Refoundation:

ARTE!✱ – You wrote that, in 2011, you still believed that it was possible to hold an exhibition that did not physically discipline the quilombolas. Today I'm thinking about the São Paulo Biennial because it's an important topic for them and I know you were there. Can you say something about this statement and Choreographies of the Impossible?

Françoise Vergès: When I said that, I thought it was possible to really do it the way we wanted, not just to show something about the quilombolas and slavery, but to do it differently, very densely, so that there would really be change. It is not necessary to tell the story that has not been told, because this is being done, it is really to change completely. And I realized that it wasn't possible because we are not free. So, the museum is not a space of freedom, it needs to be outside of it, in a place that we would have created as a place of freedom, at least for a while, maybe for a long time. That's still what I think today.

At the Biennale there are things that are absolutely fantastic and there is a real desire and drive for something beyond. And the fact that you have the Homeless Movement is really something close to a proposal that goes beyond the field of art. But it's still a Biennale. I'm not saying we shouldn't do it or that it would be bad. I don't have a virus to judge, but my point is that we know enough today that we should do something else. We know enough, as we have worked on post-colonial and decolonial strategies, on representation, analyzing images, producing texts. But we are at a decisive moment in which it is really necessary to take a leap of imagination, to escape the Western norm.

Many people expected, since this is the first time that the Biennale's curatorship has been majority black, that there would be a revolution. But when it opened, people realized that it is still a biennial, after all that is the rule….

This is what I say: the impossibility within the system of allowing you to go beyond the limits. You can transform the space, not put the table and chair in the same place in the patriarchal master's house. And this already causes challenges to the perspective of the way we circulate in space, but the wall is still there. We haven't challenged the system yet. We remain within the system. We do things differently and they are incredible, but as I say, it's time to go further, because otherwise space imposes a certain way of being.

Sometimes yes, but, let's say documenta fifteen, in 2022, was very surprising when rethinking the use of spaces, because people slept and cooked in the museum, there was a place for children. In my opinion, they completely changed the structure.

Yes, they occupied the space they were given in a different way, and with this occupation in a different way, they were effectively contesting, challenging the system. When you can't change the walls, you change the content and documenta last year tried to do that. So, what you can do if you are inside a given space is to transform it into a quilombo or rethink that space based on that city, but within that environment that was built by social forces that are racist, patriarchal, using the space in the same way possible.

I was at Ocupação 9 de Julho, and there is a space of freedom there, where life is being invented, life in the sense that what we have outside is not life. So for me, spaces of freedom don't necessarily occur in a museum or a biennale.

But at least the document pointed out that there are possibilities…

Yes, there are possibilities. But really, what I want to say is that you need to give people the power to actually grab and do whatever they want. I suggested to a friend in Paris that we do a neighborhood biennale with people from that neighborhood. We need to start with the people, the neighbors will be the curation team and we will work with them. We may also know the best way to do this or that, but we can work together. This would be the type of biennial, all based on the residents of a neighborhood.

At the same time, there is a kind of paradox in working with art, since in Ocupação 9 de Julho what they put inside the Reocupa gallery is, in some way, conventional art, with frames...

In fact, that's the debate I'm going to. We were never represented, our voices were not heard, so we will participate, but then the model is so hegemonic that we end up doing what was done before, just showing different things on the wall. In the end we don't know how to do anything different.

So this is where I want us to be now: what we will do. We want to show some memories and how are we going to do it? If we are falling back into the Western mode, that is understandable, after all we have been doing this work for a while, there will be some idea from the Western tradition that we will borrow. But we need to free our minds from this. I have worked a lot with artists and do collective workshops. We always notice how quickly we get back to normal. So, it is this movement of radical imagination that we have to face now.

We have to unlearn…

Yes! It's so hard, you know? At one point, I did an exercise about what a decolonial museum would be like four years ago. The answer was: let's change the text. I said no, because of course we can bring more diversity and different texts, but it will still be the same architecture. The main house has to be demolished. For me the issue of architecture is very important because I see that every public space is being designed in such a way that when you enter you know what you are entering and behave as you are expected to behave in that space. It is the dictatorship of architecture.

In your book you cite Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed as a tool for unlearning…

Yes, I think pedagogy is important because we have to retrain our senses about what we see, how we hear, how we smell, how we change our senses, because we all have a strategic education to serve capital. We need to say it differently, look differently and listen differently. So a pedagogy is necessary in the sense that relearning, unlearning and learning again is necessary. We need to listen to each other. In the workshop I say there are no stupid ideas. If an idea is very simple, maybe we can do it in a different way, or after a long discussion we conclude that it doesn't work and abandon that idea, but then if we abandon it we know why. It means that it is not the idea that will be most important, but the way we decide that needs to be the key to the process. ✱