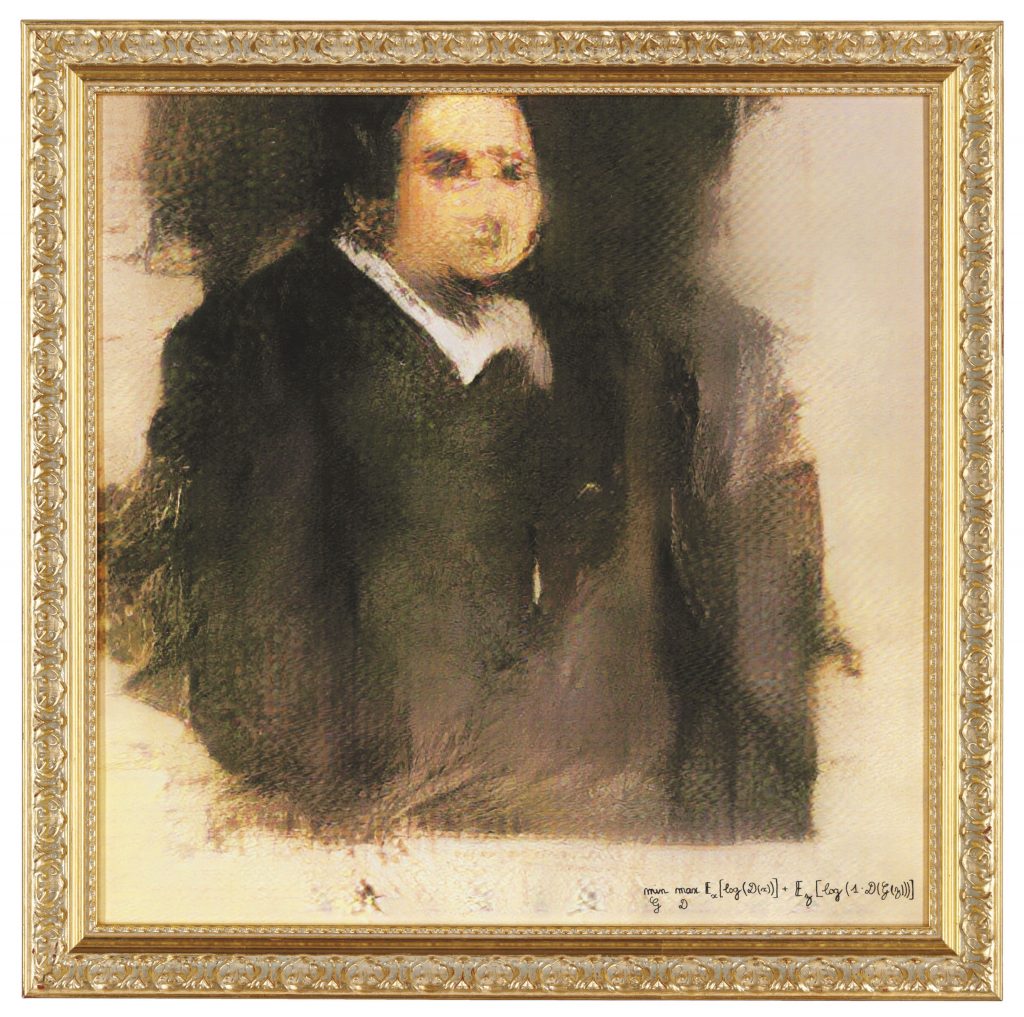

On October 25, 2018, the renowned auction house Christie's put up for sale a work made using an Artificial Intelligence (AI) program. Portrait of Edmond Belamy ended up being auctioned for U$ 432.500 (approximately R$ 2,5 million) – about 45 times its estimated value. In place of the artist's name, however, the blurred portrait was signed with the equation used to generate it. This fact was not stopped by Christie's to increase the buzz about its own auction; in a text published by the house it was reported: “This portrait is not the product of a human mind”. However, the formula used by AI to generate Portrait of Edmond Belamy was created by the human minds that make up the Parisian arts collective Obvious. Regardless, the work was the first to use an AI program to go under the hammer at a major auction house, attracting significant media attention and some speculation about what Artificial Intelligence means for the future of art.

For the past 50 years, artists have been using AI to create, notes Ahmed Elgammal, a professor at the Department of Computer Science at Rutgers University. According to him, One of the most prominent examples of this is the work of Harold Cohen and his creation program called AARON; another is the case of the American Lillian Schwartz, a pioneer in the use of computer graphics in art, who also experimented with AI. What, then, generated the speculations mentioned above about Portrait of Edmond Belamy? “The work auctioned at Christie's is part of a new wave of AI art that has appeared in recent years. Traditionally, artists who use computers to generate art have had to write detailed code that specifies the “rules for the desired aesthetic,” explains Elgammal. “In contrast, what characterizes this new wave is that algorithms are configured by artists to 'learn' aesthetics by looking at many images using machine learning technology. The algorithm then generates new images that follow the learned aesthetic,” he adds. The most used tool for this is GANs, an acronym for Generative Adversarial Networks (or Generative Adversary Networks), introduced by Ian Goodfellow in 2014. In the case of Portrait of Edmond Belamy, the Obvious collective used a database of fifteen thousand portraits painted between the XNUMXth and XNUMXth centuries. From this collection, as Elgammal points out, the algorithm fails to make correct imitations of the “pre-cured input” and instead generates distorted images.

“It is plausible that AI will become more common in art as the technology becomes more widely available,” says art critic and former Frieze editor Dan Fox in an interview with arte!brasileiros. “Most likely, AI will simply coexist with painting, video, sculpture, performance, sound and whatever artists want to use,” he adds. Fox also points out that we must not forget that “the average artist, at the moment, is not able to access this technology. Most can barely pay their rent and bills. This world of auction prices is so divorced from the life of the average artist that it must be recognized that whoever is currently working with AI is coming from a position of economic power or access to research institutions.” While the enthusiasm with Portrait of Edmond Belamy may come packed with mottos of progress and yearning for the “future” and innovation, the art critic indicates that, behind the smoke and mirrors, in the end, “AI will be of interest to the art industry if human beings can make money from it.”

Can a robot be creative?

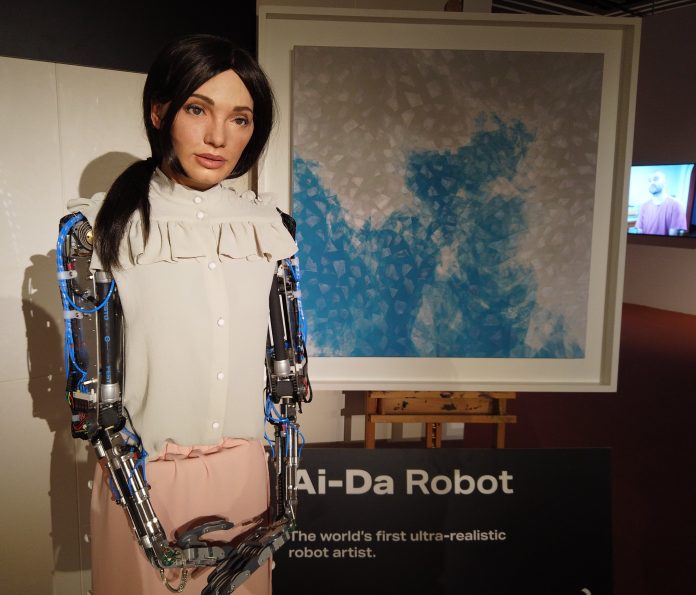

The year after Christie's was sold, Ai-da It was completed. Named after Ada Lovelace – English mathematician renowned for writing the first algorithm to be processed by a machine – she describes herself as “the world’s first ultra-realistic, AI-powered robot artist”. Ai-Da explains that she draws using the cameras implanted in her eyes, in collaboration with humans, she paints and sculpts, and also performs. “I am a contemporary artist and I am contemporary art, at the same time”, recognizes Ai-Da, and soon after, she poses the question that her audience should already be asking: “How can a robot be an artist?”. Although the question at first may seem intricate, there is another level of this questioning that is more challenging: “Can a robot be creative?”

Also in 2003, author and science journalist Matthew Hutson explored the topic in his master's thesis at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). In Artificial Intelligence and Musical Creativity: Calculating the Beethoven Tenth, he argues that “computers simulate human behavior using shortcuts. They may look human on the outside (they can write jokes or poems), but they work differently under the hood. Facades are props, not supported by real understanding. They use patterns of arrangement of words, notes and lines, but they find those patterns using statistics and cannot explain why they are there.” Hutson lists three main reasons for this: “First, computers run on different hardware than the human brain. Gelatinous brains full of neurons and flat silicon wafers full of transistors will never behave the same and will never be able to 'run the same software'. Second, we humans don't understand each other well enough to translate 'our software' to another piece of hardware. Third, computers are disembodied and understanding requires physically living in the world.” On the last topic, he ponders that particular qualities of human intelligence result directly from the particular physical structure of our brains and bodies. “We live in an analog (continuous, infinitely detailed) reality, but computers use digital information made up of finite numbers of ones and zeros.”

When asked whether the 2003 thesis holds up after almost two decades, Hutson responds to the arte!brasileiros that even today would not necessarily describe current AI artistic productions as creative, regardless of whether they are visually or semantically interesting, because not even Artificial Intelligence understands that it is making art or expressing something deeper. As Seth Lloyd, a professor of mechanical engineering and physics at MIT, would put it, "Raw information processing power does not mean sophisticated information processing power." Philosopher Daniel C. Dennett explains that “these machines do not (yet) have the goals, strategies or capacities for self-criticism and innovation that would allow them to transcend their databases through reflective thinking about their own reasoning and their own goals”. However, Hutson reiterates, “these may be human-centered concepts; AI can evolve to be as creative as humans, but in a completely different way, so we wouldn't recognize its creativity, nor it ours.”

Can culture lose jobs to AI?

“Nowadays, when cars and refrigerators are full of microprocessors and much of human society revolves around computers and cell phones connected by the internet, it seems prosaic to emphasize the centrality of information, computing and communication”, notes Lloyd in an article for Slate. We have reached a point of no return, and for the next century, the question of machine creativity is just one of many uncertainties about technology. More palpable, for now, is the possible unemployment crisis triggered by advances in AI alongside robotics.

A 2013 study conducted by researchers at the University of Oxford found, for example, that nearly half of all US jobs were at risk of being fully automated within the next two decades. On a global scale, by 2030, at least twenty million jobs could be replaced by robots, according to a more recent analysis by Oxford Economics. This 2019 analysis also warns of the greater risk of repetitive and/or mechanical work – “where robots can perform tasks faster than humans” – being eliminated, while jobs that require more “compassion, creativity and social intelligence” are more likely. to continue to be performed by humans. As the art world is not just made up of curators and collectors, you have to be concerned too. Earlier this year, during the pandemic, Tim Schneider, market editor for the portal Artnet, warned about this: “What happens when you combine mass layoffs, a willingness to minimize in-person interactions for health reasons, and willingness of technology entrepreneurs to make deep discounts on their devices so that they can guarantee greater profit potential in the cultural sector?”.

Adding the qualitative to the quantitative perspective, presented by Oxford Economics, the historian and philosopher Yuval Noah Harari would add the nature of the work and its specialization to the equation: “Let’s say you move most production from Honduras or Bangladesh to the US and Germany – because human wages are no longer part of the equation [in a scenario where automation and AI take up jobs now conducted by humans] – and it's cheaper to produce the shirt in California than in Honduras. So what will the people there do? And you might say, 'OK, but there will be a lot more jobs for software engineers.' But we are not teaching kids in Honduras to be software engineers.”

Agents or tools? AI and ethics

Estimates related to automation seem to be more reasonable. Beyond that, it's hard to have a clear picture for the future of AI, whether in terms of creativity or awareness. “Technological foresight is particularly risky,” says Lloyd, “as technologies progress through a series of refinements, are held back by obstacles, and overcome by innovation. Many obstacles and some innovations can be anticipated, but others cannot.”

For Dennett, for example, in the long term, “strong AI”, or artificial general intelligence, is possible in principle, but not desirable. “The much narrower AI, which is practically possible today, is not necessarily bad. But it presents its own set of dangers,” he warns. According to the philosopher, we do not need conscious artificial agents – what he refers to as “strong AI” – as there is an excess of conscious natural agents, enough to handle whatever tasks must be reserved for these “special and privileged entities”. "; on the contrary, we would need tools smart.

As a justification for not producing conscious artificial agents, Dennett considers that “however autonomous they may become (and, in principle, they may be as autonomous, as gifted with self-improvement and creation as anyone), they do not share with us natural agents. conscious, our vulnerability or mortality. In his statement, he echoes the writing of the father of cybernetics, Norbert Wiener, who, cautiously, reiterated: “The machine that is similar to the jinn (genius), which can learn and can make decisions based on its learning, so none will be compelled to make the decisions that we should have made, or those that will be acceptable to us.”

Regarding the ethical development of AI, according to the co-director of the Human-Centered AI Institute at Stanford University, Fei-Fei Li, it is necessary to welcome the multidisciplinary studies of AI, in a cross-pollination. with economics, ethics, law, philosophy, history, the cognitive sciences, and so on, “because there is so much more that we need to understand in terms of the ethical, social, human, and anthropological impact of AI.” In the academic field, hutson suggests that “conferences and journals can guide what is published, taking into account this broader impact of technology during peer review and requiring submissions to address ethical issues”. Taken together, he points out, funding agencies and internal review boards at universities and companies could step in to shape research at an early stage. In the post-publication stage of scientific findings, “regulations can ensure that companies do not sell harmful products and services, and laws or treaties can mandate that governments do not implement them.”

*Modifications have been made to the article for clarity.

![The [non] market of inclusion: ableism in the world of the arts Horizontal photo, black and white. In the midst of the choreography, João Paulo Lima has both hands and the only knee on the floor, keeping his back aligned, on a plank over his knee. He's in profile. He uses a costume that refers to the practices of bondage and sadomasochism, with most of the skin exposed, semi-nude. This photo is a still of the show DEVOTEES, presented in the program Zona de Criação, from the Cultural Hub of Ceará PORTO DRAGÃO.](https://artebrasileiros.com.br/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Devotees-4-Reproducao-218x150.png)