Phear more than a month after opening the exhibition Museum of Everything, in the Glass House, Julio Villani presents the public with yet another of his creations. Starting this Saturday (14/10), Villani will take the work to the historic Morumbi Chapel Paradise (here you embroider here you pay), a large embroidery – 1520 x 520 cm – with an allusion to the verses of the poet Manoel de Barros.

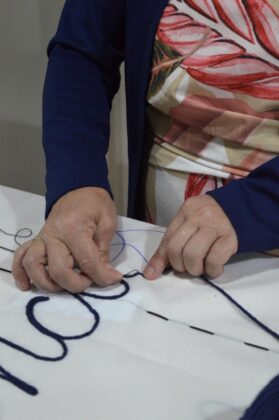

It took two months to complete the work, carried out in Lina Bo Bardi's studio, at Casa de Vidro, by seamstresses from Paraisópolis introduced to Villani by Costurando Sonhos, a social business created to welcome and empower women in the community through training in cutting. and sewing.

The project is curated by Roberta Saraiva, and the pre-production of the work Paradise (here you embroider, here you pay) was made at Centro Universitário Belas Artes, in collaboration with students Beatriz Cereser, Laura Del'Acqua, Pedro Avila, Vinicius Amaral and Thais Borducchi.

For three weeks – from Saturday (14th) until November 4th – an educational program will allow the public to make a double visit, crossing the 200 meters that separate the Chapel and the Glass House.

A arte!brasileiros spoke with Júlio Villani. Read next:

ARTE!✱ - In the book It's a game, critic Michael Asbury made observations about the singular diversity of his work: this diversity would be less linked to materials and supports than to a thought that “seeks to establish a dialogue with the history of Brazilian and international art”. To what extent is the work presented at Capela do Morumbi a continuation of this creative process? Or do we have a turning point, a rupture?

Júlio – I don’t know if I’m trying to establish a dialogue with the histories of Brazilian and international art, that is, I don’t know to what extent I do it intentionally. If this appears in my work, it is certainly as a result of the existence, within me, of multiple and intersecting influences. And not just from the art world. After all, we are what we live, and we do what we are.

I learned to use a brush by attending fine arts schools in three countries, but from my father I learned how to fence a pasture. I know how to make bronze sculptures, but I also know how to make gambiarra, and my sculptures with mined objects are certainly an extension of the toys I made, as a child. My first trip to Europe was due to the desire to see the great masters of Western painting up close, but I carry in my eyes, with equal weight, the work of Master Valentim. At some point, these different parts of me found a way to amalgamate and coexist.

Michael Asbury, who also lives with one foot there and the other here, perhaps found it easy to see, as in a mirror, the fact that in me “Brazilian and international art dialogue”. In fact, in this same book, he says that my Birds saw almost ready-mades the moment I turn one almost French artist, an almost French artist. It's an image that I like, above all because it brings the idea of a continuum, of a gradual passage, of a permanent in-between that allows us to retreat or advance in one direction or another, modifying the balance – São Paulo, Parisian, farm boy, city man, artist, hobbyist of gambiarra – depending on the moment in life.

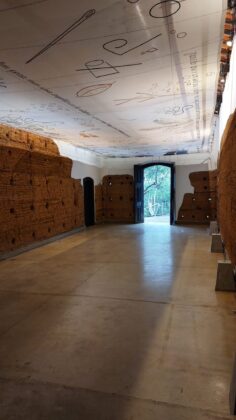

O Paradise Created for the Morumbi Chapel, it does not seem to me to be a turning point, but it is part of this continuity. The technique was developed when I made a site-specific work for the Thoronet Abbey, in 2019. I was invited by the curator, Jean de Loisy, to make an installation of embroidered sheets. But, upon visiting the place – a huge dormitory, which housed all the monks of a Cistercian community – it seemed clear to me that everyone shared the same dream. And, therefore, they deserved to be covered by the same and single giant sheet (the work measured approximately 23 x 8 meters).

As I live precisely in this back and forth, while I was working on this work there, I wondered what the parallel would be in Brazil. Remembering that it was 2019, the country was being carried away on a rocket by a speech putting God above all, while, below, “life, mere half of nothing, asked for solutions and explanations” (paraphrasing Caetano and Gil in New Cinema).

In other words, if in France I used a milky way full of texts around the eternity of the meaning of words, in Brazil it seemed essential to talk about the concreteness of life: this, here and now, and not the hypothetical paradise promised to and by “ good men” who did us so much harm. It is, therefore, more in this sense, of weaving together different realities, than of weaving a dialogue between the history of Brazilian and international art, that I think my work fits into.

ARTE!✱ - Paradise also brings an appropriation of images, texts and objects, a process considered customary in your most recent production? If so, what objects and what do they echo, reverberate, from your poetics or your worldview?

Villani – Paradise It's an embroidered yard, made of leaves and worms, pebbles and specks. Yes, my vision greatly reverberates, which consists of finding and affirming that in the inventory of the world there are no impurities, that everything can contain poetry. Although leaves and worms cannot be considered appropriations, in a multiple and diffuse way – perhaps due to the support, perhaps the medium, perhaps the fact that it is a fabric that covers us – I think that, finally, the work does have something of appropriation. . Not directly, but perhaps as a result of a process of continuous anthropophagy, which I happily claim: I have ingested and continue to digest a thousand influences.

I am therefore surprised to find that Paradise perhaps it resonates, at least in me, with other mantles that are part of my visual and affective collection: those of Bispo do Rosário, an inventory of the world through objects and words. You Parangolés by Hélio Oiticica, which are a call to action; or even that of Divider, by Lygia Pape, but here as if demanding that we reach up to break the fabric with our heads.

As for the appropriation of texts, I like to imagine that words are poetic traps; combi