NDon’t invite Gaucho businessman Justo Werlang to give the works from his collection to a collective – regardless of the eventual curatorial focus – that ends up mixing the works of the different artists that make up his collection. Yes, invite him to an exhibition dedicated to just one of the artists he collects. An exhibition like this reveals the careful way in which Werlang prepares his collection, an exercise that involves a certain proximity to the artist, close observation of what is continuous and cohesive in the person's trajectory, as well as attention to possible inflection points, the possible ruptures over time.

“Don’t invite”, of course, is a force of expression and blague. If requested to loan a work from the collection, Werlang readily responds, as long as the artist agrees to participate in the exhibition. The same goes for a possible exhibition of works in your collection: it is accepted, if the artists accept it. However, if a “collection display” is requested, then “it is necessary that the concept, which organizes the collection, can be perceived in the exhibition set up”, says Werlang to arte!brasileiros. “In other words, a very significant set of works by each of the artists is presented, in order to understand the artistic journey, the constituent elements of each artist’s very personal language, the issues brought to light, their intention and their thoughts” .

Werlang considers that, however, for this purpose, a significant amount of work is necessary, something quite difficult to carry out, due to the physical space and budget. The solution to showing the collection, he says, is for the exhibition to focus on the work of one of the artists.

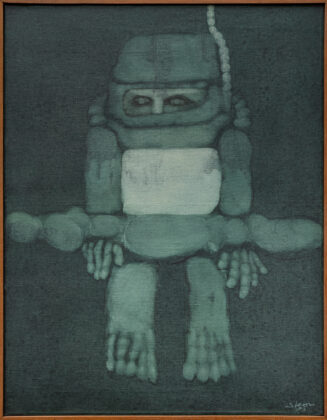

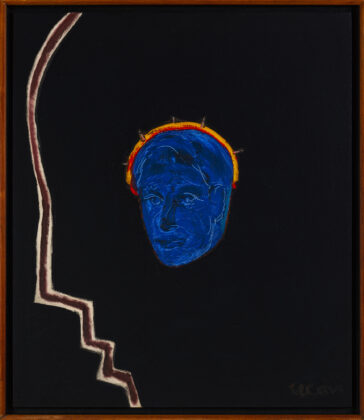

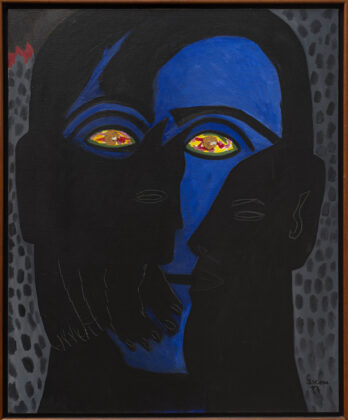

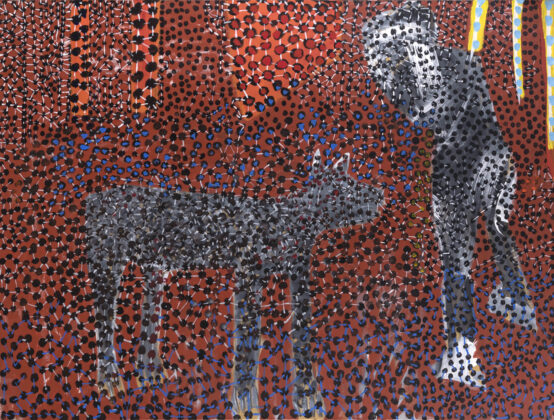

That said, an exemplary display of Werlang's modus operandi is the exhibition Trap to capture dreams, which runs until 22/10 at Farol Santander in Porto Alegre (RS) and features 63 paintings by Siron Franco (75), from Goiás, one of the (few) names that join the list of artists in the collection of the businessman from Rio Grande do Sul . Curated by Gabriel Pérez-Barreiro, who was curator of the 33rd Bienal de São Paulo, the exhibition is Farol Santander's second look at the logic of Werlang's collecting. The first took place in 2017, with the work of Karin Lambrecht belonging to the businessman. In your dream team There are also Iberê Camargo, Xico Stockinger, Nelson Felix, Daniel Senise, Mauro Fuke and Felix Bressan, with creations acquired over around three decades.

The first invitation to hold an exhibition of its collection at Farol Santander (then Santander Cultural) occurred in 2016. “I understand that it would be possible to hold a show of works from the collection, but not an exhibition of the collection”, says Werlang. In such a way, the businessman assesses, the exhibition would not reflect his purposes as a collector, his objective of, “through a significant set of works, enabling the perception of the artistic journey of each of the artists, highlighting the set of visual words generated and used, the very personal language of each one, the issues they deal with, the thoughts present and expressed there”, he states. “And, even in the case of notebooks, studies, sketches, drawings, fulfill the purpose [of revealing] the genesis of the work”.

Em Trap to capture dreams 50 years of Franco's career are followed, in an exhibition with seven sections: Cosmos, Secrets, Myths, Man, Biomes, Violence e Cesium, which brings together one of Franco's most notorious works: his series on the environmental and human catastrophe caused in 1987, in Goiânia, by the incorrect handling, by recyclable collectors, of a radiotherapy device, which led to the radioactive contamination of several people with the isotope Cesium-137.

The centers house Franco's figurative works, as well as abstract ones and also the borders between one style and another, through which Siron Franco focuses on life, art and society. Pérez-Barreiro named the groups and outlined a first selection of works. “Due to your generosity, you allowed me to suggest the inclusion of some of the works. Certainly because I collected like this, [followed] so closely, the history, the reason, the construction of each of the works in the collection, which were very close to me”, ponders the businessman. One of Franco's oldest works, Argonaut (1973), is on display at Farol Santander, as well as one of the most recent, The big network, this year.

WERLANG

Graduated in Business Administration from PUC-RS (1977) and in Law from UFRGS (1978), Justo Werlang is 67 years old. A businessman, he is the managing partner of GAWerlang – Gestão e Ambiente Ltda, a company focused on sustainable development. Its relevance in the art panorama in Brazil goes beyond the notorious disciplined and judicious collecting. The capillarity of its institutional action is immediately evident. Werlang participated in the creation of the Iberê Camargo Foundation (1995) – where he was director and vice-president (1995 to 2008), president-director (2016 to 2020), advisor (1995 to 2016), and is currently director.

The businessman was also at the forefront of the creation of the Fundação Bienal do Mercosul (1995), where he was president-director (1995 to 1997 and 2006 to 2008) and vice-president director (2003 to 2005). Since 1997 he has been part of the Board of Directors of the Fundação Bienal do Mercosul, which he currently chairs (2023 to 2024). Outside of Rio Grande do Sul, he served as vice-president at Fundação Bienal de São Paulo (2009 to 2016) and its director (2017 to 2018). Read below other excerpts from the interview given by Justo Werlang to arte!brasileiros:

ARTE!✱ – How did your collecting start?

Justo Werlang – What existed at the beginning, around 30 years ago, was not a collection, but a set of works. When Iberê Camargo's work began, there was a break, which required me to remove, I don't know, 80% of the works I had at home. The guiding thread of the collection appears, let's say, about three years after we acquired the first Iberê. Then, over time, form a significant volume in which the artist's journey can be seen. So when they asked me to show the collection, I said no, because it was a very young collection, a collection that was too young for its purpose.

ARTE!✱ – One of these invitations came from Farol Santander, back in 2016. How was your resistance overcome?

Werlang – The issue is that the concept of the collection falls apart as someone chooses one or another work from within and mixes the artists. It will not present the collection, but works from it. Because the collection is constituted by the guiding line, by the objective. So, Santander invited me to exhibit the collection, I said no, but then I replied that, if they wanted, they could exhibit an artist, because then they would be exhibiting the collection.

ARTE!✱ – Your collecting also presupposes a dialogue with the artists, in which you seek to understand their narratives. How does this conversation take place and what are the possible consequences for you and the artist?

Werlang – The collection is currently active among living artists, especially Siron, Nelson Félix, Daniel Senise, Karin Lambrecht and Mauro Fuke, who continue producing. My collection system requires me to continually interact with each of these artists, and this ends up intertwining other relationships, such as emotional relationships, friendship relationships, participation in projects. So, this participation in projects started even before we had the collection, when I started financing the production of some sculptors, in the early 1990s. Like Xico Stockinger and Gustavo Nakle. But I keep works by other artists at home, such as Vasco Prado and Nakle, which do not make up the collection. They are part of the collection of works.

ARTE!✱ – Why do you choose not to have foreign artists in your collection?

Werlang – It’s a question of access to the work, to the artist. I even thought about having works by an artist based in Madrid, but it is unfeasible to create the collection in the same way as I do, by a foreign artist in the country.

ARTE!✱ – How did your institutional career begin?

Werlang – Gustavo Nakle, Maria Tomazelli and other artists met in a place called Poleto, to drink beer. There they discussed the fact that they were outside the center, in São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro. And they discussed the possibility of participating more in the national art market. One of the ideas was to hold a biennial. One day they met a lady called Maria Benites, an Argentine based in Porto Alegre. And Maria Benites is a workhorse, a director. She got involved with this group and said: “You need the support of the state and the support of the business community.” She had contact with Maria Helena Gerdau Johannpeter, Jorge's wife, and from then on Jorge got involved, held a dinner to which businesspeople, gallerists, artists and representatives of public authorities were invited. In this process, people appeared who wanted to be president of what would become the Mercosul Biennial. And the guys they intended to be, the artists didn't even want to know about them. Maria Benites started saying that I had to take over the position. I said that if Jorge agreed for us to form a council, a group without a president, then I would participate. I was forced to take over, then I had to overcome several inertia. There was no human capital to create an assembly, there was no lighting, no architecture, there was nothing. So starting to do this was very complicated, it took a lot of my time.

ARTE!✱ – In 1995, the same year in which the process to create the Biennale began, the project for the Iberê Camargo Foundation was also beginning. How was your performance at the time?

Werlang – Jorge invited me to be treasurer there. I accepted because, after all, we were partners and I had to do it. I don't like being a treasurer, it wasn't my skill. I stayed at Iberê for 13 years, very active, until we opened the building [in 2008].

ARTE!✱ – And how did your connection with the São Paulo Biennial come about?

Werlang – When we opened the headquarters of the Iberê Camargo Foundation, I requested my removal and, coincidentally, I left the presidency of the 6th Mercosul Biennial. After 12 months without participating in any event related to the visual arts, I decided to go to the opening of the SP-Arte fair. In the corridors, I met Júlio [Landmann, who had presided over the 24th Bienal], and Heitor Martins [who presided over the 29th and 30th editions, from 2009 to 2012]. In the conversation that followed with Heitor, he said that he had received the invitation to set up a board for the Biennale, and asked me what I would say about the invitation, at a time when many had given up on the institution. My answer was that yes, I should accept it, as the Biennale's contributions were much greater than the hole in which it found itself. Hector then added: “And would you be with us?” In fact, involvement in that challenge was not part of my project. I then thought about what the Biennale had meant in Iberê's career, in the career of Daniel, Siron, Karin, Nelson Felix. So, I accepted. We were a wonderful team, we argued, we didn't agree with everything, we even fought, but there was enormous commonality in the objective of repositioning the institution that harmonized everything.