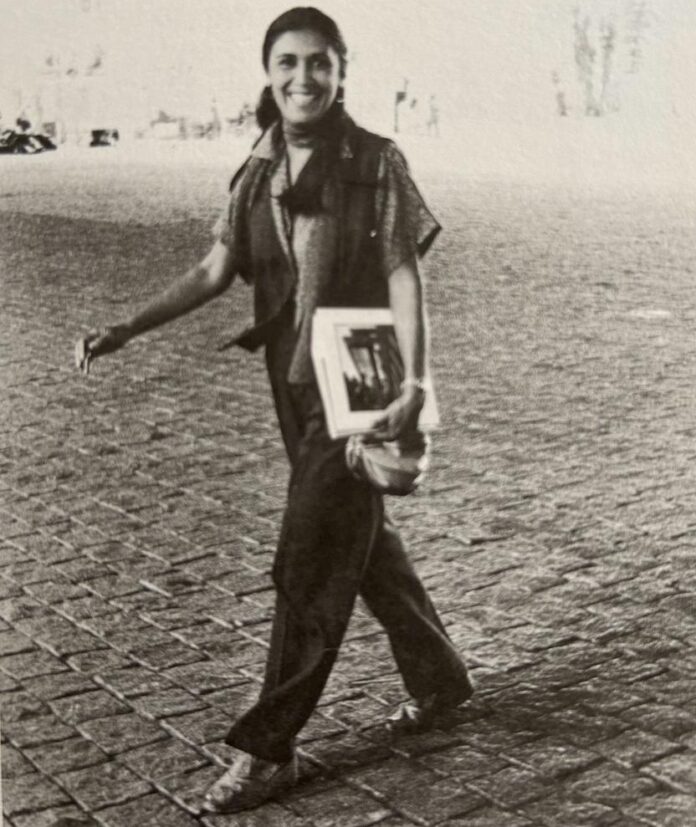

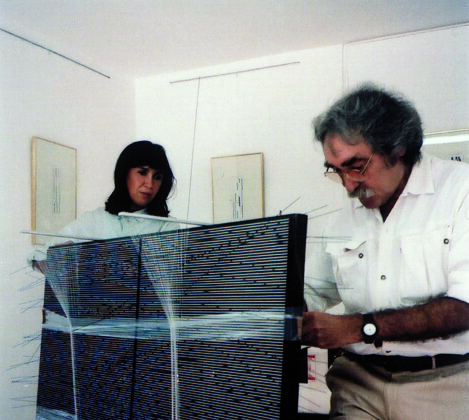

TBreath, perseverance and attitude mark the story of Raquel Arnaud, a determined woman, who in the 1970s broke through the arrogance of the male world of the art market to become one of the most successful Brazilian gallerists of the last 50 years.

Raquel was born in Guaratinguetá, where she attended primary school, and at the age of 10 she moved with her family to São Paulo, a promising city that even at that time held the São Paulo Biennial, the second most important art event of its kind on the planet.

In this new scenario, at the same time as he attends high school, he attends the São Paulo Museum of Art. “This contact with MASP was decisive for me. There I attended art history classes with Professor [Wolfgang] Pfeiffer, who opened my eyes to the subject.” In 1954 Raquel entered the Free School of Sociology and Politics, an experience that she rejected after completing the course because she preferred architecture, which she always considered something wonderful. This learning in the sociological field certainly broadens her narrative and helps her to forge the strong character she has as a gallerist.

Shortly afterwards she joins the Segall family, when she marries Oscar, the son of the modernist painter, she goes to live with him in the house designed by the architect Gregori Warchavchik, where today the Lasar Segall Museum. “Although it was brief, the period I lived with the couple, Lasar and Jenny, was fundamental for me, especially because of my relationship with Ms. Jenny. One day she asked me to help her organize the paintings by Lasar Segall (1891-1957) that would go to a traveling exhibition abroad, shortly after his death.”

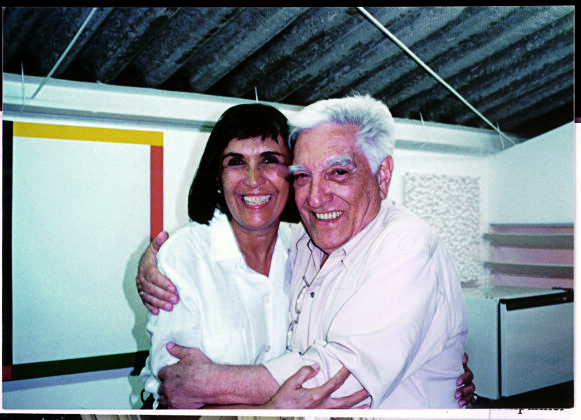

In 1968 Raquel separated from Oscar and worked with Alcântara Machado, a well-known organizer of textile fairs with fashion shows. “We worked together for some time and, when Professor Pietro Maria Bardi, director of MASP, found out that I was involved in a commercial sector, he didn't like it. He told me, “I don’t want you working with business people. My museum needs someone who knows Van Gogh.” With that Raquel joined the MASP team and Professor Bardi was very receptive to her. “Little by little I started taking on some roles within the museum, including in the exhibitions.”

Lina Bo Bardi had arrived from Bahia and Raquel worked with her. “It was a great learning experience, we slowly created very beautiful work, because Lina belonged to the vanguard of the time. She was someone who already thought differently than Bardi, a creative architect in every way.” Just remember that Tripartite Unit, a work by Max Bill that was awarded at the 1st São Paulo Biennale in 1951, had already been exhibited at MASP in 1947, four years before the Biennale, when Lina was teaching about Bauhaus, a movement to which the Swiss artist was involved.

Raquel had personal plans outside the museum's boundaries and in 1973 she left MASP and joined Mônica Filgueiras, a young woman with contagious energy, whom she met during her time at the Collectio auction house. Together they open the Graphic Arts Office, at Haddock Lobo, working with paper, engravings and drawings. In parallel, Raquel also worked at Arte Global, a gallery that belonged to Rede Globo.

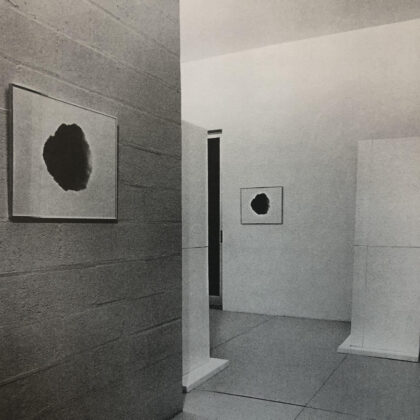

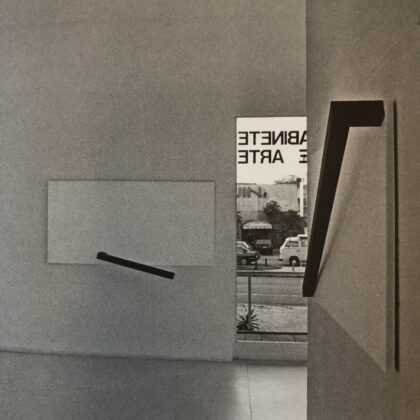

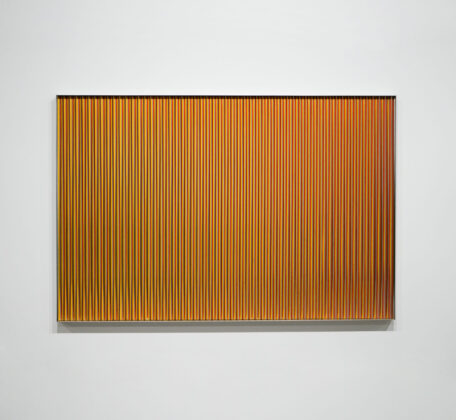

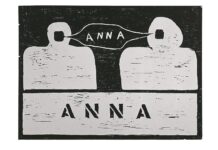

This experience was significant at that time, but she pursued a solo career, so in 1980 she announced her new gallery, the Cabinet of Art Raquel Arnaud, on Av. 9 de Julho. “It was a very good moment for me when I started exhibiting important contemporary artists.” The aesthetic dynamism of the geometrics contaminates her and the convincing theoretical impulse of Willys de Castro convinces her to embrace the movement artistically and commercially. After all, every desire to win has to identify with something strong. Thus, she approaches the work of Sérgio Camargo, Franz Weissmann, Tomie Ohtake, Willys de Castro, Hércules Barsotti, Arthur Luiz Piza, Anna Maria Maiolino, Leon Ferrari, Carmela Gross, among many others.

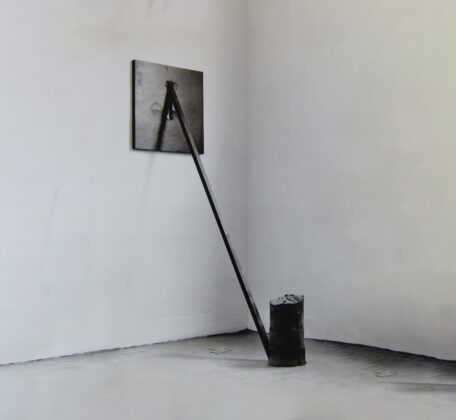

In 1977, he launched one of the landmarks of his intellectual work, the work Black box, with drawings by Julio Plaza, a Spanish artist based in São Paulo and poems by writer Augusto de Campos, recited on record by Caetano Veloso. His path, built with a leading cast, had been consolidated. The following years were successful with many exhibitions and debates. In 1980, he incorporated, as a dimension of his references, a crop of young artists already known in the market. “That was when I started working with José Resende, Waltercio Caldas, Tunga, among other talents”.

Every professional always has a character they admire as a reference, and Raquel was no different. Like many international gallerists, she is enchanted by the work of the legendary Denise René, alter ego of the arts in Paris in the 1950s/1960s. The great lady was one of the supporters of kinetic art, a fact that influenced Raquel. Under her friend's charisma, she displays works by two exponents of kinetic art, the Venezuelan artists Cruz-Diez and Jesus Soto.

One of the projects that Raquel is very proud of is the creation of the Institute of Contemporary Art (IAC). With it, she defines an expanded social space. “The idea is to make documentation on the work of Brazilian artists available for research, in addition to promoting seminars, courses and exhibitions.”

Today, with her gallery installed in a pleasant space in Vila Madalena, she maintains her conceptual model of dealing with art. She continues to build bridges with formal rigor in her choices of works and artists, especially those linked to the geometric, without leaving aside some restorative fantasies brought by other less orthodox strands.

ILLUSTRATIVE EXHIBITION A PROCESS

A long path marks the history of Galeria Raquel Arnaud which, for 50 years, has contributed to contemporary art in a unique way, as evidenced by the more than 500 exhibitions held between 1974 and 2023. The recently opened collective Raquel Arnaud Gallery – 50 years, curated by Jacopo Crivelli Visconti and deputy curator Marina Schiesari, has a documentary character by recording all the shows and artists exhibited by the gallerist over the years.

Although the art circuit today faces an emancipated public, which understands much more about art than it did 50 years ago, Jacopo Crivelli Visconti opted for an almost pedagogical exhibition in which the spectator can follow, without fear, the course of a production aimed practically at geometric abstractionism.

What seems like a disagreement is a gain. The exhibition was not just designed for experts, but designed especially for the active and participatory visitor, willing to get to know artists who nowadays would be difficult to associate with their visit to the gallery. It is latent in the assembly that the gallerist's main concern, throughout her career, was maintaining the preservation and cataloging of the works, especially in the last 20 years. The exhibition constitutes a living document of a coherent project that demonstrates how Raquel defended the artistic class. One of the examples is the creation of the IAC – Institute of Contemporary Art created to keep artists' works protected.

The idea for the exhibition was born to celebrate Raquel as a gallerist, which Jacopo guarantees to have strictly followed. The group tries to be objective, immersive and functional by delving into the archive that becomes documentary material, with which an exhibition discourse was created with different languages experimented by most renowned Brazilian artists. Behind each record of works there is a considerable number of photographs, letters, catalogues, exhibition invitations.

The choice of the timeline as an exhibition process gave the exhibition a unique character. It contains all the titles of all the exhibitions held throughout Raquel Arnaud's career, as well as all the artists who exhibited over these 50 years. Raquel regrets that for some of them she was unable to obtain complete documentation. “At the beginning of my work as a gallerist, cataloging practically did not exist, so part of what was exhibited at that time was in my head”.

The collective brings together important documents such as texts by critics, artists and curators who passed through the gallery. Jacopo emphasizes that precisely all of this makes up the second part of the project, which is the publication of a book, a compilation of texts that should be published at the end of the exhibition, next May, when the gallery's 50th anniversary is actually celebrated. “We also want to illustrate the edition with images from the exhibition. The publication will be a counterpoint to the exhibition and will be made from a large selection because Raquel worked with most Brazilian artists, critics and curators, from various periods”. He considers this compilation even more important than the exhibition.

The collective uses the timeline, with the option of chronological serialization, which at the beginning of the route works in a counterclockwise direction. The oldest documents, from 1974, are profiled on the wall and go around the ground floor. They follow the staircase that takes the visitor to the upper floor and, at this point, the clockwise direction is adopted, which continues until reaching the year 2023. In fact, these two directions meet in the works of Arthur Piza (1974) and João Trevisan (2023), in a dense plot of continuity, with one work in front of the other. Like a Möbius strip, which refers to the symbol of infinity, the works are based on a line without beginning or end.

In the process of exhibition dynamics, “it is practically impossible to hold an exhibition with all the works, so the attempt was also to maintain a certain balance”, as Jacopo observes. What unites most of these works is the eye of imagination, the matrix of a geometric passion that Raquel embraced under the influence of Willys de Castro, at the beginning of it all. In the stellar cast, there are artists who were fundamental to her on a personal level, such as Hercules Barsotti and Sérgio Camargo, two friends who she considers almost brothers. In an exercise within the conceptual process, artists appear who were symbolic in this trajectory and brought together by analogies of concepts. Raquel mentions Regina Silveira who opened up to several discussions. There are still many others like Nuno Ramos, Carlito Carvalhosa, and Frida Baraneck.

The arrow crosses decades, pointing to the international market trend always tensioned by the new, as evidenced by Tunga's work, which simultaneously dialogues with different languages. “There are works that were included in the gallery, then left, now they have returned and, as far as possible, we have managed to incorporate them”, comments Jacopo. With an atypical assembly, the works sparsely installed throughout the gallery are contextualized with the documents displayed on the wall. For the curator, the most important part of the exhibition is right on the wall.

There are historical highlights from the 1970s when everything flowed quickly. Jacopo remembers that the average exhibition during this period was three weeks, and also with elaborate catalogues, such as those by Antônio Manoel and Regina Vater. “The atmosphere of the São Paulo art market at that time was more playful and less competitive”, adds Raquel.

With the launch of the book, new reinterpretations of geometric art and its developments should put emerging characters, confrontations, achievements and reflections on the origins of this movement, which has some internationally recognized Brazilian and Spanish-American protagonists, on the agenda.