More than 100 years later, the correspondence between Einstein and Freud remains more current than ever. And, in the same universal and timeless dimension as them, today we question the limits between Law and violence, between terrorism and religious obscurantism, be it in Israel's attacks on Gaza, in the resurgence of neo-fascism and the extreme right in Europe, in the USA and in Latin America.

Einstein writes:

Potsdam, July 30, 1932

Dear Professor Freud

The proposal of the League of Nations and its International Institute for Intellectual Cooperation in Paris that I invite a person of my own choosing to a frank exchange of views on some problem of my own choosing offers me excellent opportunity to confer with you on a question which, as things stand, appears to be the most urgent of all the problems that civilization has to face.

This is the problem: is there any way to free humanity from the threat of war? It is common knowledge that, with the progress of modern science, this topic has acquired the significance of a matter of life and death for civilization, as we know it; However, despite all the commitment shown, all attempts to resolve it ended in regrettable failure.

… As for me, the habitual aim of my thought does not permit me an inner understanding of the obscure regions of human will and feeling. Thus, in the inquiry now proposed, I can do little more than seek to clarify the question in question and, by preparing the ground for the most obvious solutions, enable you to provide an elucidation of the problem with the help of your profound knowledge of man's instinctive life. .

… As a person free from nationalist prejudices, I personally see a simple way of approaching the superficial (that is, administrative) aspect of the problem: the establishment, through international agreement, of a legislative and judicial body to arbitrate any conflict that arises between nations . Each nation would submit to obedience to the orders issued by this legislative body, to resort to its decisions in all disputes, to accept its decisions unrestrictedly and to put into practice all measures that the court considered necessary for the execution of its decrees. .

Right from the start, however, I am faced with a difficulty: a court is a human institution that, in relation to the power at its disposal, is inadequate to enforce its verdicts and is very prone to seeing its decisions annulled by extrajudicial pressure. This is a fact we have to reckon with; law and power inevitably go hand in hand, and legal decisions come closer to the ideal justice demanded by the community (in whose name and in whose interests these verdicts are pronounced), insofar as the community effectively has the power to impose respect for its legal ideal. “…

…” The failure, despite the evident sincerity, of all efforts over the last decade to achieve this goal leaves no room for doubt that major psychological factors are at play that paralyze such efforts. Some of these factors are easier to detect. The intense desire for power, which characterizes the ruling class in every nation, is hostile to any limitation of its national sovereignty. This hunger for political power is accustomed to flourishing in the activities of another group, whose aspirations are of an economic, purely mercenary nature. I refer especially to that small but determined group existing in each nation, made up of individuals who, indifferent to social conditions and controls, consider war, the manufacture and sale of weapons simply as an opportunity to expand their personal interests and expand your personal authority.

Recognition of this fact, however, is simply the first step towards an assessment of the current situation. Another question soon arises: how is it possible for this small group to bend the will of the majority, which is resigned to losing and suffering from a situation of war, in the service of the ambition of a few? (When speaking of the majority, I do not exclude soldiers, of all ranks, who chose war as a profession, in the belief that they are serving to defend the highest interests of their race and that attack is often the best means of defense).

It seems that an obvious answer to this question would be that the minority, the current ruling class, has the schools, the press and, generally, also the Church, under its power. This makes it possible to organize and dominate the emotions of the masses and make them an instrument of this minority.

Still, even this answer does not provide a complete solution. Hence a new question arises: how do these mechanisms manage to awaken such extreme enthusiasm in men, to the point of them sacrificing their lives? There can be only one answer. It is because man contains within himself a desire for hatred and destruction.

In normal times, this passion exists in a latent state, it emerges only in abnormal circumstances: it is, however, relatively easy to awaken it and raise it to the power of collective psychosis. Perhaps therein lies the crucial point of the entire complex of factors we are considering, an enigma that only an expert in the science of human instincts can solve.

With that, we come to our last question. Is it possible to control the evolution of man's mind, so as to make him proof against the psychoses of hatred and destructiveness? Here I am not just referring to the so-called uneducated masses. Experience proves that it is, above all, the so-called Intelligentzia that is most inclined to give in to these disastrous collective suggestions, since the intellectual does not have direct contact with the rude side of life, but finds it in its easiest synthetic form in printed page.

To conclude: so far I have only spoken about wars between nations, those known as international conflicts. I am, however, well aware that the aggressive instinct operates in other forms and under other circumstances. (I think of civil wars, for example, due to religious intolerance, in previous times, nowadays, however, due to social factors; furthermore, also of the persecution of racial minorities.)

My insistence on what is the most typical, most cruel and extravagant form of conflict between men was deliberate, as here we have the best opportunity to discover ways and means of making any armed conflict impossible.

I know that in your writings we can find answers, explicit or implicit, to all aspects of this urgent and obsessive problem. But it would be of the greatest use to us all if you presented the problem of world peace from the perspective of your most recent discoveries, as such a presentation could well mark the path for new and fruitful methods of action.

Very cordially,

Albert EINSTEIN

In response, Freud writes:

Vienna, September 1932

Dear Professor Einstein,

When I learned that you intended to invite me to an exchange of views on a subject that interested you and that seemed to deserve the interest of others besides you, I readily accepted. I was hoping that you would choose a problem located on the frontiers of what is currently knowable, a problem in relation to which each of us, physicist and psychologist, could have our own special angle of approach, and in which we could find ourselves, on the same terrain, although starting from different directions.

You caught me by surprise, however, when you asked what can be done to protect humanity from the curse of war. Initially I was frightened by the thought of my – I almost wrote 'our' – inability to deal with what seemed to be a practical problem, a matter for Statesmen. Later, however, I realized that you had proposed the question, not as a natural scientist and physicist, but as a philanthropist: you were following the suggestion of the League of Nations, just as Fridtjof Nansen, the polar explorer, took up the task of helping the hungry and homeless victims of world war.

Furthermore, I considered that I was not being asked to propose practical measures, but simply to define the problem to avoid war as it appears in the eyes of a psychological scientist. Also on this point, you have said almost everything there is to say on the subject. Although you have anticipated me, I will be happy to follow in your wake and I will be satisfied with confirming everything you said, expanding it to the best of my knowledge or my conjectures.

You started with the relationship between law and power. There can be no doubt that this is the correct starting point of our investigation. But, allow me to replace the word 'power' with the more naked word 'violence'?

Currently, law and violence appear to us as antitheses. However, it is easy to show that one developed from the other, and if we go back to the earliest origins and examine how these things happened, the problem is easily solved. Forgive me if, in these considerations that follow, I tread familiar and commonly accepted ground, as if this were new. The thread of my arguments demands it.

It is, therefore, a general principle that conflicts of interest between men are resolved through the use of violence. This is what happens throughout the animal kingdom, from which man has no reason to exclude himself. In the case of man, conflicts of opinion undoubtedly also occur that can reach the rarest nuances of abstraction and that seem to require some other technique for their solution. This is, however, an additional complication.

In the beginning, in a small human horde, it was the superiority of muscular strength that decided who had possession of things or who made their will prevail. Muscular strength was soon supplemented and replaced by the use of instruments: the winner was the one who had the best weapons or the one who had the greatest skill in handling them.

From the moment weapons were introduced, intellectual superiority began to replace brute muscular strength; but the ultimate objective of the struggle remained the same “one or other faction had to be compelled to abandon its pretensions or its objections, because of the damage that had been inflicted on it by the dismantling of its force.

This objective was achieved more completely if the victor's violence eliminated his opponent forever, that is, if he killed him. This had two advantages: the vanquished could not reestablish his opposition and his fate would dissuade others from following his example. Furthermore, killing an enemy satisfied an instinctual inclination, which I will mention later.

The intention to kill would be opposed by the reflection that the enemy could be used to perform useful services, if he were left alive and in a state of intimidation. In this case, the victor's violence was content with subduing, rather than killing, the vanquished. This was the beginning of the idea of sparing the life of an enemy, but from then on the victor had to rely on the hidden thirst for revenge of the defeated opponent and sacrificed part of his own safety.

This was, therefore, the initial situation of the facts: domination by anyone who had power greater than domination by brute violence or violence supported by the intellect. As we know, this regime was modified in the course of evolution. There was a path that extended from violence to law or law.

What path was this? I think there was only one: the path that led to the recognition of the fact that the superior strength of a single individual could be countered by the union of several weak individuals: union makes strength. Violence could be defeated by unity, and the power of those who united now represents the law, as opposed to the violence of the individual alone. We see, therefore, that the law is the strength of a community.

However, it is still violence, ready to turn against any individual who opposes it. It works by the same methods and pursues the same objectives. The only real difference lies in the fact that what prevails is no longer the violence of an individual, but the violence of the community.

In order for the transition from violence to this new right or justice to be effected, however, a psychological condition had to be fulfilled. The union of the majority should be stable and lasting. If it had only been put into practice for the purpose of combating an isolated and dominant individual, and had been dissolved after his defeat, nothing would have been accomplished.

The next person, who considered himself superior in strength, would once again try to establish dominance through violence, and the game would be repeated ad infinitum. The community must maintain itself permanently, must organize itself, must establish regulations to anticipate the risk of rebellion and must institute authorities to ensure that these regulations, that the laws are respected, and to supervise the execution of legal acts of violence.

The recognition of an entity of interests such as these has led to the emergence of emotional bonds between members of a group of people united by common feelings, which are the true source of their strength. I believe that, with this, we already have all the essential elements: violence supplanted by the transfer of power to a larger unit, which is held together by emotional ties between its members. What remains to be said is nothing more than an amplification and a repetition of this fact.

The situation is simple as long as the community consists of only a few equally strong individuals. The laws of such an association will determine the degree to which, if the security of communal life is to be guaranteed, each individual must give up his personal freedom to use his force for violent purposes.

A state of equilibrium of this kind, however, is only conceivable theoretically. In reality, the situation is complicated by the fact that, from its beginnings, the community encompasses elements of unequal strength, men and women, parents and children, and soon, as a consequence of war and conquest, it also begins to include victors and defeated, who become masters and slaves.

The justice of the community then begins to express unequal degrees of power in force within it. Laws are made by and for the governing members and leave little room for the rights of those in a state of subjection.

From that time on, there were two factors at work in the community that were a source of concern regarding matters of the law, but which tended, at the same time, to a greater growth of the law.

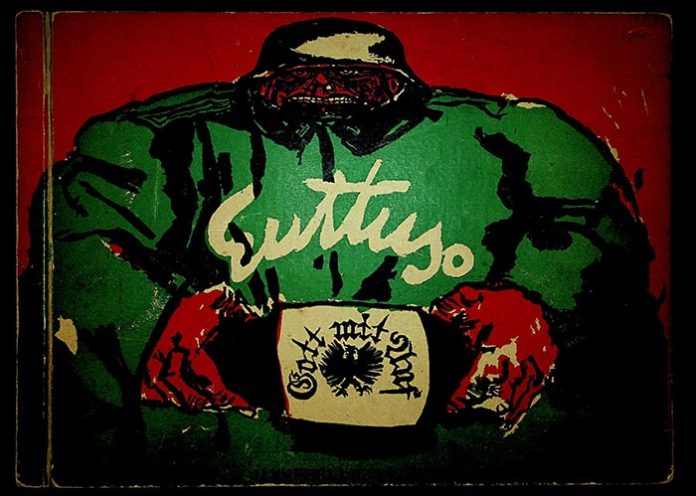

34,4 cm x 24,8 cm, Donation Museum of Modern Art of São Paulo.

Firstly, attempts are made by certain holders of power to place themselves above the prohibitions that apply to

Everyone, that is, seeks to escape from rule by law to rule by violence.

Secondly, the oppressed members of the group make constant efforts to obtain more power and see some changes made in this regard recognized in the law, that is, they push to move from unequal justice to equal justice for all. This second tendency becomes especially important if a real shift in power occurs within the community, as may occur as a result of a number of historical factors. In this case, the law can gradually adapt to the new distribution of power; or, as happens more frequently, the ruling class refuses to admit change and rebellion and civil war ensue, with a temporary suspension of the law and new attempts at a solution through violence, ending with the establishment of a new system of laws.

There is still a third source from which changes in the law can arise, and which is invariably expressed through peaceful means: it consists in the cultural transformation of the members of the community. This, however, is properly part of another correlation and must be considered later.

We see, therefore, that the violent solution of conflicts of interest is not avoided even within a community. Everyday needs and common interests, inevitable where people live together in one place, tend, however, to bring these struggles to a quick conclusion, and under such conditions there is an increasing probability of finding a peaceful solution. Furthermore, a quick look at the history of the human race reveals an endless series of conflicts between one community and another, or several others, between larger and smaller units, between cities, provinces, races, nations, empires, which were almost always formed by force. of weapons. Wars of this kind end either by looting or by the complete annihilation and conquest of one of the parties.

It is impossible to establish any general judgment of wars of conquest. Some, like those undertaken by the Mongols and Turks, brought nothing but harm. Others, on the contrary, contributed to the transformation of violence into law, by establishing larger units, among which the use of violence became impossible and in which a new system of laws resolved conflicts. In this way, the conquests of the Romans gave the countries close to the Mediterranean the invaluable pax Romana, and the ambition of the French kings to expand their dominions created a peacefully united and flourishing France.

Paradoxical as it may seem, it must be admitted that war could be a far from inadequate means of establishing the eagerly desired reign of everlasting peace, for it is in a position to create the great units within which a powerful central government makes further wars impossible. However, it fails in this regard, as the results of conquest are generally short-lived: newly created units fall apart again, most often due to a lack of cohesion between the parts that were united by violence.

Furthermore, until today the unifications created by the conquest, although of considerable extent, were only partial, and the conflicts between them gave rise, more than ever, to violent solutions. The result of all these war efforts was, therefore, only that the human race exchanged the numerous and truly endless smaller wars for large-scale wars, which are rare, but much more destructive. If we turn to our own times, we reach the same conclusion that you reached by a shorter route. Wars will only be avoided with certainty if humanity unites to establish a central authority that will be granted the right to arbitrate all conflicts of interest. Two distinct requirements are clearly involved in this: creating a supreme authority and endowing it with the necessary power. One without the other would be useless. The League of Nations is intended to be an instance of this kind, but the second condition has not been fulfilled: the League of Nations has no power of its own, and can only acquire it if the members of the new union, the different States, are willing to give it up. And, at the moment, prospects in this regard seem scarce.

The institution of the League of Nations would be completely unintelligible if it ignored the fact that there was a courageous attempt, such as has rarely (perhaps never on such a scale) been made before. It is an attempt to base authority on an appeal to certain idealistic attitudes of the mind (i.e., coercive influence), which otherwise rests on the possession of force. We have already seen that a community is held together by two things: the coercive force of violence and the emotional bonds between its members. If one of the factors is absent, it is possible that the community will still be maintained by the other factor.

The ideas appealed to can, of course, only be important if they express important affinities between the members, and one may wonder how much force these ideas can exert. History teaches us that, to some extent, they were effective. For example, the idea of panhellenism, the sense of being superior to the barbarians from beyond the borders, an idea that was expressed with such vigor in the amphictyonic council, in the oracles and in the games, was strong to the point of mitigating the warlike customs among the Greeks, though, of course, not strong enough to prevent warlike dissensions between the different parts of the Greek nation, or even to prevent a city or confederation of cities from allying with the Persian enemy, in order to obtain an advantage against some rival.

The identity of feelings among Christians, although it was powerful, failed, at the time of the Renaissance, to prevent Christian States, both large and small, from seeking the sultan's help in their wars against each other. And there is currently no idea that is expected to exercise such a unifying authority. In reality, it is very evident that the national ideals, by which nations are governed today, act in the opposite direction.

Some people tend to prophesy that it will not be possible to put an end to the war as long as the communist way of thinking has not found universal acceptance. But this objective, in any case, is currently very remote, and could perhaps only be achieved after the most terrible civil wars. Therefore, at present, the attempt to replace real force with the force of ideas seems to be doomed to failure. We will be making a wrong calculation if we ignore the fact that the law was originally brute force and that, even today, it cannot do without the support of violence.

I will now add some observations to your comments. You express surprise at the fact that it is so easy to inflame enthusiasm for war in men, and introduce the suspicion that something in their activity requires something, an instinct of hatred and destruction, which cooperates with the efforts of the merchants of war. . Here too I can only express my complete agreement. We believe in the existence of an instinct of this nature, and during the last few years we have really been busy studying its manifestations.

Allow me to take this opportunity to present to you a part of the theory of instincts which, after many hesitant attempts and many vacillations of opinion, was formulated by those who work in the field of psychoanalysis?

According to our hypothesis, human instincts are of only two types: those that tend to preserve and unite what we call 'erotic', in exactly the same sense in which Plato uses the word 'Eros' in his Symposium, or 'sexual'. ', with a deliberate expansion of the popular conception of 'sexuality'; and those that tend to destroy and kill, which we group as aggressive or destructive instinct.

As you see, this is nothing but a theoretical formulation of the universally known opposition between love and hate, which may perhaps have some basic relationship with the polarity between attraction and repulsion, which plays a role in your area of knowledge. However, we should not be too hasty in introducing ethical judgments of good and evil.

Neither of these two instincts is less essential than the other; the phenomena of life arise from the confluent or mutually contrary action of both. Now, it is as if an instinct of one kind could hardly operate in isolation; it is always accompanied, or, as we say, amalgamated by a certain quantity on the other side, which modifies its objective, or, in certain cases, makes it possible to achieve that objective. Thus, for example, the instinct of self-preservation is certainly erotic in nature; However, you must have aggressiveness at your disposal to achieve your purpose.

Thus, the love instinct, when directed towards an object, also needs some contribution from the dominance instinct, in order to obtain possession of that object. The difficulty of isolating the two types of instinct in their real manifestations is, in fact, what has hitherto prevented us from recognizing them.

If you want to follow me a little longer, you will see that human actions are subject to another complication of a different nature. Very rarely is an action the work of a single instinctive impulse (which must be composed of Eros and destructiveness). In order to make an action possible, there must, as a rule, be a combination of these compound motives. This, long ago, was noticed by an expert in his subject, Professor GC Lichtenberg, who taught physics in Göttingen, during our classicism, although, perhaps, he was even more notable as a psychologist than as a physicist. He invented a 'compass of reasons', as he wrote: 'The reasons that lead us to do something could be arranged in the manner of a compass rose and given names in a similar way: for example, 'bread-bread-fame' or 'fame-fame-bread'. So that, when human beings are incited to war, they can have a whole range of reasons for letting themselves go, some noble, others vile, some frankly declared, others never mentioned. There is no reason to list them all. Among them is certainly the desire for aggression and destruction: the countless cruelties that we encounter in history and in our everyday lives attest to its existence and its strength.

The satisfaction of these naturally destructive impulses is facilitated by their mixing with other motives of an erotic and idealistic nature. When we read about the atrocities of the past, it is often as if idealistic motives merely served as an excuse for destructive desires; and sometimes, for example, in the case of the cruelties of the Inquisition, it is as if the idealistic motives had come to the fore in consciousness, while the destructive ones had given them an unconscious reinforcement. Both can be true.

I am afraid that I may be abusing your interest, which, after all, is directed towards the prevention of war and not towards our theories. I would, however, like to dwell a little longer on our destructive instinct, whose popularity is by no means equal to its importance. As a consequence of a little speculation, we were able to suppose that this instinct is active in every living creature and seeks to lead it to annihilation, to reduce life to the original condition of inanimate matter.

Therefore, it deserves, in all seriousness, to be called the death instinct, while erotic instincts represent the effort to live. The death instinct becomes a destructive instinct when, with the help of special organs, it is directed outwards, towards objects. The organism preserves its own life, so to speak, by destroying the life of others. A part of the death instinct, however, continues to be active within the organism, and we have tried to attribute numerous normal and pathological phenomena to this internalization of the destruction instinct. We were even blamed for the heresy of attributing the origin of conscience to this inward deviation of aggressiveness.

You will realize that it is not absolutely irrelevant whether this process goes too far: it is positively insane. On the other hand, if these forces turn to destruction in the external world, the organism will be relieved and the effect must be beneficial. This would serve as biological justification for all the reprehensible and dangerous impulses we struggle with. It must be admitted that they are closer to Nature than our resistance, for which it is also necessary to find an explanation.

Perhaps it may seem to you that our theories are a kind of mythology and, in this case, not a pleasant mythology. However, do not all sciences ultimately arrive at a kind of mythology like this? Can't the same be said today about your physics? For our immediate purposes, therefore, this is all that follows from what has been said: there is no point in trying to eliminate the aggressive inclinations of men.

According to what we are told, in certain privileged regions of the Earth, where nature provides in abundance everything that is necessary for man, there are people whose lives pass in the midst of tranquility, people who know neither coercion nor aggression. I can hardly believe it, and I would like to know more about such fortunate things. Bolsheviks also hope to be able to make human aggressiveness disappear by ensuring the satisfaction of all material needs and establishing equality, in other respects, among all members of the community. This, in my opinion, is an illusion. They themselves, nowadays, are armed in the most cautious manner, and the no less important method they employ to keep their adherents together is hatred against anyone beyond their borders.

In any case, as you yourself observed, there is no way to completely eliminate man's aggressive impulses; one can try to divert them to such a degree that they need not find expression in war.

Our mythological theory of instincts makes it easy for us to find the formula for indirect methods of fighting war. If the desire to join the war is an effect of the destructive instinct, the most obvious recommendation would be to oppose it to its antagonist, Eros. Everything that favors the strengthening of emotional bonds between men must act against war. These links can be of two types.

Firstly, they can be relationships similar to those relating to a loved object, although they do not have a sexual purpose. Psychoanalysis has no reason to be ashamed if it talks about love at this point, because religion itself uses the same words: 'Love your neighbor as yourself.' This, however, is more easily said than practiced.

The second emotional bond is the one that uses identification. Everything that leads men to share important interests produces this communion of feeling, these identifications. And the structure of human society is based on them, to a large extent.

A complaint you made about the abuse of authority leads me to another suggestion for indirectly combating the propensity for war. An example of the innate and irremovable inequality of men is their tendency to classify themselves into two types, that of leaders and that of followers. The latter constitute the vast majority; They need an authority that makes decisions for them and to which, for the most part, they devote unlimited submission. This suggests that more attention should be given, than has been given to date, to the education of the upper class of men endowed with an independent mentality, not susceptible to intimidation and willing to remain faithful to the truth, whose concern is to direct the dependent masses.

It is needless to say that the usurpations committed by the executive power of the State and the prohibition established by the Church against freedom of thought are not at all favorable to the formation of a class of this type. The ideal situation, naturally, would be the human community that has subordinated its instinctual life to the domain of reason. Nothing else could unite men so completely and firmly, even if there were no emotional bonds between them. However, in all likelihood this is a utopian expectation. There is no doubt that other indirect methods of avoiding war are more feasible, although they do not promise immediate success. It's worth remembering that disturbing image of the mill that grinds so slowly that people can starve to death before it can provide their flour.

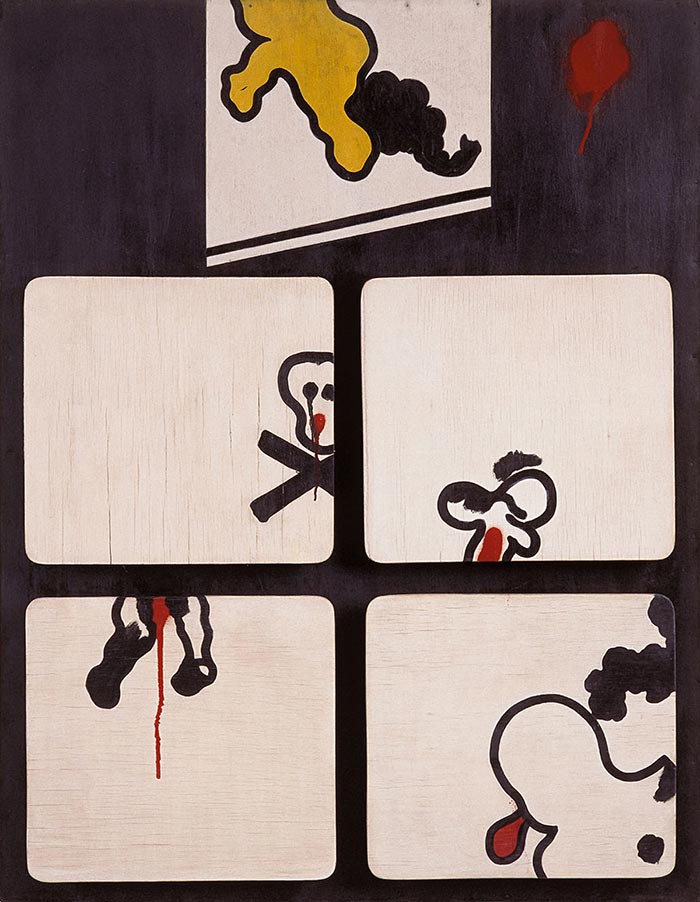

oil and latex on wood, 120,6 cm x 93,3 cm x 6,8 cm,

MAC USP acquisition.

The result, as you see, is not very fruitful when a disinterested theorist is called upon to give his opinion on an urgent practical problem. It is better for a person, in any special case, to devote himself to meeting the danger with all the means at hand.

I would, however, like to discuss one more issue that you do not mention in your letter, which interests me in particular. Why did you, I and so many other people rebel so violently against the war? Why don't we accept it as just one of life's many calamities? After all, it seems to be a very natural thing, it seems to have a biological basis and is difficult to avoid in practice.

There is no reason to be surprised that I raise this question. For the purposes of an investigation like this, one could, perhaps, be permitted to wear a mask of supposed obliviousness. The answer to my question will be that we react to war in this way, because everyone has the right to their own life, because war puts an end to lives full of hope, because it leads individual men into humiliating situations, because it compels them , against his will, to kill other men and because he destroys precious material objects, produced by the work of humanity.

Other reasons could be presented, such as that, in its current form, war is no longer an opportunity to achieve the old ideals of heroism, and that, due to the improvement of instruments of destruction, a future war could involve the extermination of one of the antagonists or, perhaps, both. All this is true, and so incontestably true, that one cannot but feel perplexed at the fact that the war has not yet been unanimously repudiated.

Undoubtedly, debate around some of these points is possible. One may ask whether a community should not have the right to dispose of the lives of individuals; not all war is condemnable in equal measure; Since there are countries and nations that are prepared for the merciless destruction of others, these others must be armed for war. But I will not dwell on any of these aspects; They do not constitute what you wish to discuss with me, and I have something different in mind.

I think the main reason we rebel against war is that we can't do anything else. We are pacifists because we are obliged to be so, for organic, basic reasons. And so, we have difficulty finding arguments that justify our attitude.

No doubt this requires some explanation. I believe it is the following. Over incalculable periods of time, humanity has undergone a process of cultural evolution (I know that some prefer to use the term 'civilization'). It is to this process that we owe the best of what we have become, as well as a good part of what we suffer from.

Although its causes and beginnings are obscure and its outcome is uncertain, some of its characteristics are easy to perceive. Perhaps this process is leading to the extinction of the human race, as in more than one sense it impairs sexual function; Uneducated people and backward layers of the population are already multiplying faster than the highly educated layers.

Perhaps the process can be compared to the domestication of certain animal species, and it is undoubtedly accompanied by physical changes; but we have not yet become familiar with the idea that the evolution of civilization is an organic process of this order. The psychic changes that accompany the process of civilization are notorious and unequivocal. They consist of a progressive displacement of instinctive purposes and a limitation imposed on instinctive impulses. Sensations that were pleasant for our ancestors have become indifferent or even intolerable for us; There are organic reasons for changes in our ethical and aesthetic ideals.

Among the psychological characteristics of civilization, two appear to be the most important: the strengthening of the intellect, which is beginning to govern the life of instinct, and the internalization of aggressive impulses with all their consequent advantages and dangers. Now, war constitutes the most obvious opposition to the psychic attitude that was instilled in us by the process of civilization, and for this reason we cannot avoid rebelling against it; We simply can no longer conform to it. This is not just an intellectual and emotional repudiation. We, pacifists, have a constitutional intolerance to war, let's say, an idiosyncrasy exacerbated to the highest degree.

Indeed, it seems that the lowering of aesthetic standards in war plays hardly a smaller role in our revolt than its cruelties.

And how long will we have to wait until the rest of humanity also becomes pacifist? There's no way to say it. But it may not be utopian to expect that these two factors, cultural attitude and the justified fear of the consequences of a future war, will result, within a foreseeable time, in putting an end to the threat of war.

We cannot guess by what paths or shortcuts this will take place. But one thing we can say: everything that stimulates the growth of civilization works simultaneously against war.

I hope you will forgive me if what I said disappointed you, and with the expression of all esteem, I subscribe. ✱

Cordially,

Sigmund FREUD

A dialogue between Einstein and Freud: why the war?/ presentation by Deisy de Freitas Lima Ventura, Ricardo Antônio Silva Seitenfus – Santa Maria: FADISMA, 2005. FADISMA – Faculty of Law of Santa Maria

About the copyright relating to this publication:

The texts of Einstein and Freud are in the public domain.

Based on the Brazilian (Complete Works of Sigmund Freud, Standard Brazilian edition. Rio de Janeiro: Imago, 1976. v. XXII) and French (DAVID, Christophe. Einstein e Freud. Pour quoi la guerre? Paris: Payot & Rivages, 2005).

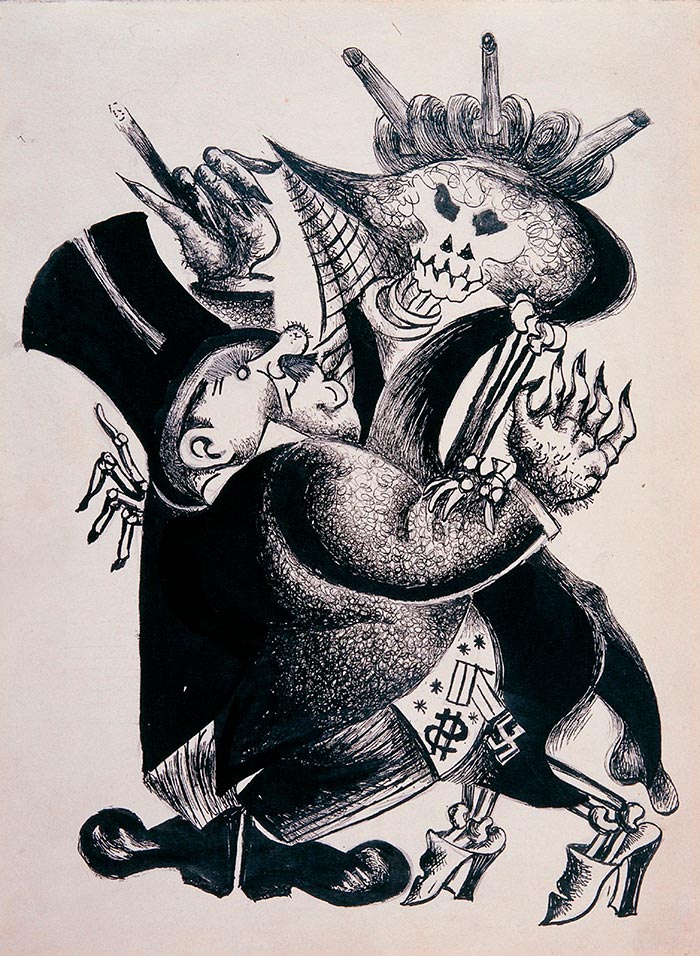

* Images

These images are photographic reproductions of the works that are currently on display in the Fraturated Times exhibition at the São Paulo Museum of Contemporary Art, MAC-USP